From the writer’s personal investigations of this subject in different sections of the country, the damage to forest products of various kinds from this cause seems to be far more extensive than is generally recognized. Allowing a loss of five per cent on the total value of the forest products of the country, which the writer believes to be a conservative estimate, it would amount to something over $30,000,000 annually. This loss differs from that resulting from insect damage to natural forest resources, in that it represents more directly a loss of money invested in material and labor. In dealing with the insects mentioned, as with forest insects in general, the methods which yield the best results are those which relate directly to preventing attack, as well as those which are unattractive or unfavorable. The insects have two objects in their attack: one is to obtain food, the other is to prepare for the development of their broods. Different species of insects have special periods during the season of activity (March to November), when the adults are on the wing in search of suitable material in which to deposit their eggs. Some species, which fly in April, will be attracted to the trunks of recently felled pine trees or to piles of pine sawlogs from trees felled the previous winter. They are not attracted to any other kind of timber, because they can live only in the bark or wood of pine, and only in that which is in the proper condition to favor the hatching of their eggs and the normal development of their young. As they fly only in April, they cannot injure the logs of trees felled during the remainder of the year.

There are also oak insects, which attack nothing but oak; hickory, cypress, and spruce insects, etc., which have different habits and different periods of flight, and require special conditions of the bark and wood for depositing their eggs or for subsequent development of their broods. Some of these insects have but one generation in a year, others have two or more, while some require more than one year for the complete development and transformation. Some species deposit their eggs in the bark or wood of trees soon after they are felled or before any perceptible change from the normal living tissue has taken place; other species are attracted only to dead bark and dead wood of trees which have been felled or girdled for several months; others are attracted to dry and seasoned wood; while another class will attack nothing but very old, dry bark or wood of special kinds and under special conditions. Thus it will be seen how important it is for the practical man to have knowledge of such of the foregoing facts as apply to his immediate interest in the manufacture or utilization of a given forest product, in order that he may with the least trouble and expense adjust his business methods to meet the requirements for preventing losses.

The work of different kinds of insects, as represented by special injuries to forest products, is the first thing to attract attention, and the distinctive character of this work is easily observed, while the insect responsible for it is seldom seen, or it is so difficult to determine by the general observer from descriptions or illustrations that the species is rarely recognized. Fortunately, the character of the work is often sufficient in itself to identify the cause and suggest a remedy, and in this section primary consideration is given to this phase of the subject.

Ambrosia or Timber Beetles

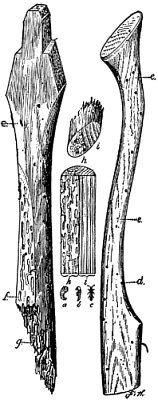

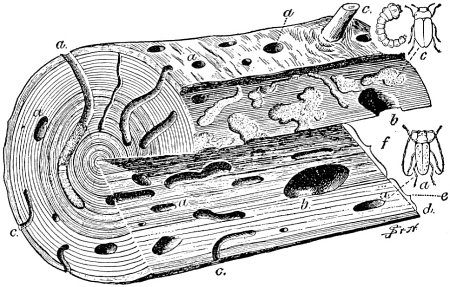

Fig. 22. Work of Ambrosia Beetles in Tulip or Yellow Poplar Wood. a, work of Xyleborus affinis and Xyleborus inermis; b, Xyleborus obesus and work; c, bark; d, sapwood; e, heartwood.

Fig. 23. Work of Ambrosia Beetles in Oak. a, Monarthrum mali and work; b, Platypus compositus and work; c, bark; d, sapwood; e, heartwood; f, character of work in wood from injured log.

The characteristic work of this class of wood-boring beetles is shown in Figs. 22 and 23. The injury consists of pinhole and stained-wood defects in the sapwood and heartwood of recently felled or girdled trees, sawlogs, pulpwood, stave and shingle bolts, green or unseasoned lumber, and staves and heads of barrels containing alcoholic liquids. The holes and galleries are made by the adult parent beetles, to serve as entrances and temporary houses or nurseries for the development of their broods of young, which feed on a fungus growing on the walls of the galleries.

The growth of this ambrosia-like fungus is induced and controlled by the parent beetles, and the young are dependent upon it for food. The wood must be in exactly the proper condition for the growth of the fungus in order to attract the beetles and induce them to excavate their galleries; it must have a certain degree of moisture and other favorable qualities, which usually prevail during the period involved in the change from living, or normal, to dead or dry wood; such a condition is found in recently felled trees, sawlogs, or like crude products.

There are two general types or classes of these galleries: one in which the broods develop together in the main burrows (see Fig. 22), the other in which the individuals develop in short, separate side chambers, extending at right angles from the primary galleries (see Fig. 23). The galleries of the latter type are usually accompanied by a distinct staining of the wood, while those of the former are not.

The beetles responsible for this work are cylindrical in form, apparently with a head (the prothorax) half as long as the remainder of the body (see Figs. 22, a, and 23, a).

North American species vary in size from less than one-tenth to slightly more than two-tenths of an inch, while some of the subtropical and tropical species attain a much larger size. The diameter of the holes made by each species corresponds closely to that of the body, and varies from about one-twentieth to one-sixteenth of an inch for the tropical species.

Round-headed Borers

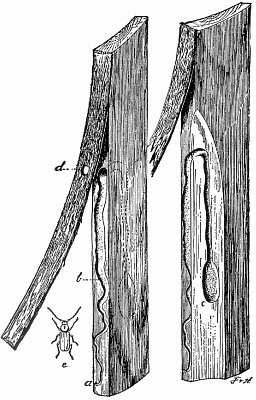

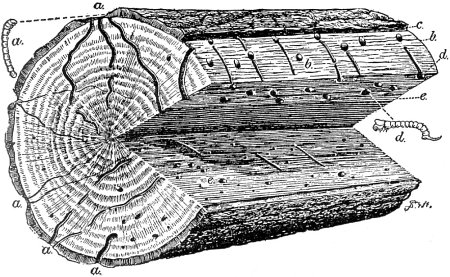

Fig. 24. Work of Round-headed and Flat-headed Borers in Pine. a, work of round-headed borer, “sawyer,” Monohammus spiculatus, natural size b, Ergates spiculatus; c, work of flat-headed borer, Buprestis, larva and adult; d, bark; e, sapwood; f, heartwood.

The character of the work of this class of wood- and bark-boring grubs is shown in Fig. 24. The injuries consist of irregular flattened or nearly round wormhole defects in the wood, which sometimes result in the destruction of valuable parts of the wood or bark material. The sapwood and heartwood of recently felled trees, sawlogs, poles posts, mine props, pulpwood and cordwood, also lumber or square timber, with bark on the edges, and construction timber in new and old buildings, are injured by wormhole defects, while the valuable parts of stored oak and hemlock tanbark and certain kinds of wood are converted into worm-dust. These injuries are caused by the young or larvae of long-horned beetles. Those which infest the wood hatch from eggs deposited in the outer bark of logs and like material, and the minute grubs hatching therefrom bore into the inner bark, through which they extend their irregular burrows, for the purpose of obtaining food from the sap and other nutritive material found in the plant tissue. They continue to extend and enlarge their burrows as they increase in size, until they are nearly or quite full grown. They then enter the wood and continue their excavations deep into the sapwood or heartwood until they attain their normal size. They then excavate pupa cells in which to transform into adults, which emerge from the wood through exit holes in the surface. This class of borers is represented by a large number of species. The adults, however, are seldom seen by the general observer unless cut out of the wood before they have emerged.

Flat-headed Borers

The work of the flat-headed borers (Fig. 24) is only distinguished from that of the preceding by the broad, shallow burrows, and the much more oblong form of the exit holes. In general, the injuries are similiar, and effect the same class of products, but they are of much less importance. The adult forms are flattened, metallic-colored beetles, and represent many species, of various sizes.

Timber Worms

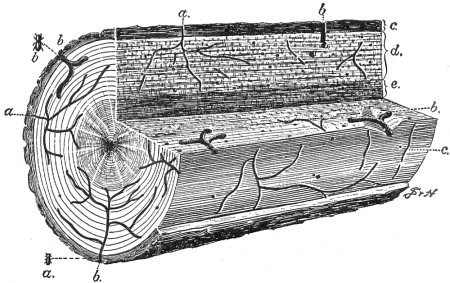

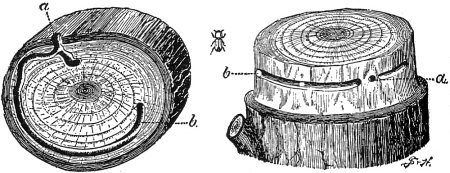

Fig. 25. Work of Timber Worms in Oak. a, work of oak timber worm, Eupsalis minuta; b, barked surface; c, bark; d, sapwood timber worm, Hylocoetus lugubris, and work; e, sapwood.

The character of the work done by this class is shown in Fig. 25. The injury consists of pinhole defects in the sapwood and heartwood of felled trees, sawlogs and like material which have been left in the woods or in piles in the open for several months during the warmer seasons. Stave and shingle bolts and closely piled oak lumber and square timbers also suffer from injury of this kind. These injuries are made by elongate, slender worms or larvae, which hatch from eggs deposited by the adult beetles in the outer bark, or, where there is no bark, just beneath the surface of the wood. At first the young larvae bore almost invisible holes for a long distance through the sapwood and heartwood, but as they increase in size the same holes are enlarged and extended until the larvae have attained their full growth. They then transform to adults, and emerge through the enlarged entrance burrows. The work of these timber worms is distinguished from that of the timber beetles by the greater variation in the size of holes in the same piece of wood, also by the fact that they are not branched from a single entrance or gallery, as are those made by the beetles.

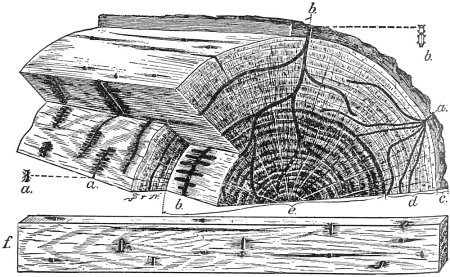

Fig. 26. Work of Powder Post Beetle, Sinoxylon basilare, in Hickory Poles, showing Transverse Egg Galleries excavated by the Adult, a, entrance; b, gallery; c, adult.

Fig. 27. Work of Powder Post Beetle, Sinoxylon basilare, in Hickory Pole. a, character of work by larvae; b, exit holes made by emerging broods.

Powder Post Borers

The character of the work of this class of insects is shown in Figs. 26, 27, and 28. The injury consists of closely placed burrows, packed with borings, or a completely destroyed or powdered condition of the wood of seasoned products, such as lumber, crude and finished handle and wagon stock, cooperage and wooden truss hoops, furniture, and inside finish woodwork, in old buildings, as well as in many other crude or finished and utilized woods. This is the work of both the adults and young stages of some species, or of the larval stage alone of others. In the former, the adult beetles deposit their eggs in burrows or galleries excavated for the purpose, as in Figs. 26 and 27, while in the latter (Fig. 28) the eggs are on or beneath the surface of the wood. The grubs complete the destruction by boring through the solid wood in all directions and packing their burrows with the powdered wood. When they are full grown they transform to the adult, and emerge from the injured material through holes in the surface. Some of the species continue to work in the same wood until many generations have developed and emerged or until every particle of wood tissue has been destroyed and the available nutritive substance extracted.

Fig. 28. Work of Powder Post Beetles, Lyctus striatus, in Hickory Handles and Spokes. a, larva; b, pupa; c, adult; d, exit holes; e, entrance of larvae (vents for borings are exits of parasites); f, work of larvae; g, wood, completely destroyed; h, sapwood; i, heartwood.

Conditions Favorable for Insect Injury—Crude Products—Round Timber with Bark on

Newly felled trees, sawlogs, stave and heading bolts, telegraph poles, posts, and the like material, cut in the fall and winter, and left on the ground or in close piles during a few weeks or months in the spring or summer, causing them to heat and sweat, are especially liable to injury by ambrosia beetles (Figs. 22 and 23), round and flat-headed borers (Fig. 24), and timber worms (Fig. 25), as are also trees felled in the warm season, and left for a time before working up into lumber.

The proper degree of moisture found in freshly cut living or dying wood, and the period when the insects are flying, are the conditions most favorable for attack. This period of danger varies with the time of the year the timber is felled and with the different kinds of trees. Those felled in late fall and winter will generally remain attractive to ambrosia beetles, and to the adults of round- and flat-headed borers during March, April, and May. Those felled in April to September may be attacked in a few days after they are felled, and the period of danger may not extend over more than a few weeks. Certain kinds of trees felled during certain months and seasons are never attacked, because the danger period prevails only when the insects are flying; on the other hand, if the same kinds of trees are felled at a different time, the conditions may be most attractive when the insects are active, and they will be thickly infested and ruined.

The presence of bark is absolutely necessary for infestation by most of the wood-boring grubs, since the eggs and young stages must occupy the outer and inner portions before they can enter the wood. Some ambrosia and timber worms will, however, attack barked logs, especially those in close piles, and others shaded and protected from rapid drying.

The sapwood of pine, spruce, fir, cedar, cypress, and the like softwoods is especially liable to injury by ambrosia beetles, while the heartwood is sometimes ruined by a class of round-headed borers, known as “sawyers.” Yellow poplar, oak, chestnut, gum, hickory, and most other hardwoods are as a rule attacked by species of ambrosia beetles, sawyers, and timber worms, different from those infesting the pines, there being but very few species which attack both.

Mahogany and other rare and valuable woods imported from the tropics to this country in the form of round logs, with or without bark on, are commonly damaged more or less seriously by ambrosia beetles and timber worms.

It would appear from the writer’s investigations of logs received at the mills in this country, that the principal damage is done during a limited period—from the time the trees are felled until they are placed in fresh or salt water for transportation to the shipping points. If, however, the logs are loaded on a vessel direct from the shore, or if not left in the water long enough to kill the insects, the latter will continue their destructive work during transportation to other countries and after they arrive, and until cold weather ensues or the logs are converted into lumber.

It was also found that a thorough soaking in sea-water, while it usually killed the insects at the time, did not prevent subsequent attacks by both foreign and native ambrosia beetles; also, that the removal of the bark from such logs previous to immersion did not render them entirely immune. Those with the bark off were attacked more than those with it on, owing to a greater amount of saline moisture retained by the bark.

How to Prevent Injury

From the foregoing it will be seen that some requisites for preventing these insect injuries to round timber are:

1. To provide for as little delay as possible between the felling of the tree and its manufacture into rough products. This is especially necessary with trees felled from April to September, in the region north of the Gulf States, and from March to November in the latter, while the late fall and winter cutting should all be worked up by March or April.

2. If the round timber must be left in the woods or on the skidways during the danger period, every precaution should be taken to facilitate rapid drying of the inner bark, by keeping the logs off the ground in the sun, or in loose piles; or else the opposite extreme should be adopted and the logs kept in water.

3. The immediate removal of all the bark from poles, posts, and other material which will not be seriously damaged by checking or season checks.

4. To determine and utilize the proper months or seasons to girdle or fell different kinds of trees: Bald cypress in the swamps of the South are “girdled” in order that they may die, and in a few weeks or months dry out and become light enough to float. This method has been extensively adopted in sections where it is the only practicable one by which the timber can be transported to the sawmills. It is found, however, that some of these “girdled” trees are especially attractive to several species of ambrosia beetles (Figs. 22 and 23), round-headed borers (Fig. 24) and timber worms (Fig. 25), which cause serious injury to the sapwood or heartwood, while other trees “girdled” at a different time or season are not injured. This suggested to the writer the importance of experiments to determine the proper time to “girdle” trees to avoid losses, and they are now being conducted on an extensive scale by the United States Forest Service, in co-operation with prominent cypress operators in different sections of the cypress-growing region.

Saplings

Saplings, including hickory and other round hoop-poles and similiar products, are subject to serious injuries and destruction by round- and flat-headed borers (Fig. 24), and certain species of powder post borers (Figs. 26 and 27) before the bark and wood are dead or dry, and also by other powder post borers (Fig. 28) after they are dried and seasoned. The conditions favoring attack by the former class are those resulting from leaving the poles in piles or bundles in or near the forest for a few weeks during the season of insect activity, and by the latter from leaving them stored in one place for several months.

Stave, Heading and Shingle Bolts

These are attacked by ambrosia beetles (Figs. 22 and 23), and the oak timber worm (Fig. 25, a), which, as has been frequently reported, cause serious losses. The conditions favoring attack by these insects are similiar to those mentioned under “Round Timber.” The insects may enter the wood before the bolts are cut from the log or afterward, especially if the bolts are left in moist, shady places in the woods, in close piles during the danger period. If cut during the warm season, the bark should be removed and the bolts converted into the smallest practicable size and piled in such manner as to facilitate rapid drying.

Unseasoned Products in the Rough

Freshly sawn hardwood, placed in close piles during warm, damp weather in July and September, presents especially favorable conditions for injury by ambrosia beetles (Figs. 22, a, and 23, a). This is due to the continued moist condition of such material.

Heavy two-inch or three-inch stuff is also liable to attack even in loose piles with lumber or cross sticks. An example of the latter was found in a valuable lot of mahogany lumber of first grade, the value of which was reduced two thirds by injury from a native ambrosia beetle. Numerous complaints have been received from different sections of the country of this class of injury to oak, poplar, gum, and other hardwoods. In all cases it is the moist condition and retarded drying of the lumber which induces attack; therefore, any method which will provide for the rapid drying of the wood before or after piling will tend to prevent losses.

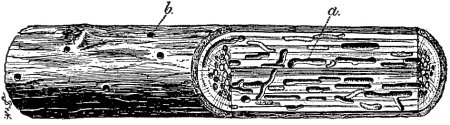

It is important that heavy lumber should, as far as possible, be cut in the winter months and piled so that it will be well dried out before the middle of March. Square timber, stave and heading bolts, with the bark on, often suffer from injuries by flat- or round-headed borers, hatching from eggs deposited in the bark of the logs before they are sawed and piled. One example of serious damage and loss was reported in which white pine staves for paint buckets and other small wooden vessels, which had been sawed from small logs, and the bark left on the edges, were attacked by a round-headed borer, the adults having deposited their eggs in the bark after the stock was sawn and piled. The character of the injury is shown in Fig. 29. Another example was reported from a manufacturer in the South, where the pieces of lumber which had strips of bark on one side were seriously damaged by the same kind of borer, the eggs having been deposited in the logs before sawing or in the bark after the lumber was piled. If the eggs are deposited in the logs, and the borers have entered the inner bark or the wood before sawing, they may continue their work regardless of methods of piling, but if such lumber is cut from new logs and placed in the pile while green, with the bark surface up, it will be much less liable to attack than if piled with the bark edges down. This liability of lumber with bark edges or sides to be attacked by insects suggests the importance of the removal of the bark, to prevent damage, or, if this is not practicable, the lumber with the bark on the sides should be piled in open, loose piles with the bark up, while that with the bark on the edges should be placed on the outer edges of the piles, exposed to the light and air.

Fig. 29. Work of Round-headed Borers, Callidium antennatum, in White Pine Bucket Staves from New Hampshire. a, where egg was deposited in bark; b, larval mine; c, pupal cell; d, exit in bark; e, adult.

In the Southern States it is difficult to keep green timber in the woods or in piles for any length of time, because of the rapidity which wood-destroying fungi attack it. This is particularly true during the summer season, when the humidity is greatest. There is really no easily-applied, general specific for these summer troubles in the handling of wood, but there are some suggestions that are worth while that it may be well to mention. One of these, and the most important, is to remove all the bark from the timber that has been cut, just as soon as possible after felling. And, in this, emphasis should be laid on the ALL, as a piece of bark no larger than a man’s little finger will furnish an entering place for insects, and once they get in, it is a difficult matter to get rid of them, for they seldom stop boring until they ruin the stick. And again, after the timber has been felled and the bark removed, it is well to get it to the mill pond or cut up into merchantable sizes and on to the pile as soon as possible. What is wanted is to get the timber up off the ground, to a place where it can get plenty of air, to enable the sap to dry up before it sours; and, besides, large units of wood are more likely to crack open on the ends from the heat than they would if cut up into the smaller units for merchandizing.

A moist condition of lumber and square timber, such as results from close or solid piles, with the bottom layers on the ground or on foundations of old decaying logs or near decaying stumps and logs, offers especially favorable conditions for the attack of white ants.

Seasoned Products in the Rough

Seasoned or dry timber in stacks or storage is liable to injury by powder post borers (Fig. 28). The conditions favoring attack are: (1) The presence of a large proportion of sapwood, as in hickory, ash, and similiar woods; (2) material which is two or more years old, or that which has been kept in one place for a long time; (3) access to old infested material. Therefore, such stock should be frequently examined for evidence of the presence of these insects. This is always indicated by fine, flour-like powder on or beneath the piles, or otherwise associated with such material. All infested material should be at once removed and the infested parts destroyed by burning.

Dry Cooperage Stock and Wooden Truss Hoops

These are especially liable to attack and serious injury by powder post borers (Fig. 28), under the same or similiar conditions as the preceding.

Staves and Heads of Barrels containing Alcoholic Liquids

These are liable to attack by ambrosia beetles (Figs. 22, a, and 23, a), which are attracted by the moist condition and possibly by the peculiar odor of the wood, resembling that of dying sapwood of trees and logs, which is their normal breeding place.

There are many examples on record of serious losses of liquors from leakage caused by the beetles boring through the staves and heads of the barrels and casks in cellars and storerooms.

The condition, in addition to the moisture of the wood, which is favorable for the presence of the beetles, is proximity to their breeding places, such as the trunks and stumps of recently felled or dying oak, maple, and other hardwood or deciduous trees; lumber yards, sawmills, freshly-cut cordwood, from living or dead trees, and forests of hardwood timber. Under such conditions the beetles occur in great numbers, and if the storerooms and cellars in which the barrels are kept stored are damp, poorly ventilated, and readily accessible to them, serious injury is almost certain to follow.

INDEX: Seasoning of Wood